The drawback of magnetic tape was that to get to a particular item you had to wind through the tape to locate it, which was both laborious and time-consuming. As this limitation made it difficult to use magnetic tapes in an educational context, the division was casting around for another medium that would fill this void. Dr Kramer and his team therefore embarked on research to identify a new means of detecting information on a medium that would enable quick access to any specific data there.

As Philips was the leading expert in the lighting sector, he decided to take a lamp as a source and project light onto a transparent medium with information inside the material that could be detected by this. At that time, all signals including audio or video were conveyed by analogue transmission, as digitalisation and indeed computers in general were still in their infancy. Even a calculator for performing simple multiplications, additions, subtractions and divisions required a vast array of electronics and several cubic metres of components

“Eventually, Dr Kramer was ready. Armed with a plastic disc and a mountain of electronics, he was all set to detect the signal in the disc, but the experiment did not go according to plan. All that came through was noise, prompting him to say: “We tried to look for the signals, but we saw nothing!” We were stunned. How could it that Dr Kramer's device only reproduced noise, given that we had the best Philips incandescent light bulbs to illuminate the image, and we had an excellent detector? So we tried again with another, even better, light source... but there was still only noise.”

One of the researchers suggested it was time to make some small-scale mathematical calculations. “He realised that with an incandescent light bulb, no matter how powerful this was, you'd never get enough protons on a surface of approximately one micron to transmit the signal to the sensor. We needed a more powerful light source.”

Laser technology was the obvious choice. Philips manufactured lasers but these were expensive, costing around €1,000. This time the noise disappeared, and clear simple black-and-white images appeared on the screen. In 1971, the team demonstrated their equipment to the Philips Executive Board, who decided that the technology was bound to have enormous potential for application and research should therefore continue.

"We showed them a black-and-white image and told them we would have one in colour within three months", said Dr Kramer. The Board approved the production of the disc and increased the size of the development team. Development took another six years, at the end of which we were able to show off a clear colour image and high-quality sound.

Laservision and rivals

The Audio Division grasped the resulting opportunity, deciding to develop an affordable disc player. Video disc players were then a brand-new market segment with a very promising future.In 1978, Philips joined the disc market with a new product: the 'LaserVision' laser video disc player, a gleaming box into which film buffs could insert a 30-cm optical disc.

A laser beam used FM signals to read the surface the images were encoded on. At that time, discs were still played on an analogue, nondigital system. For a new system to be successful, the film production companies had to be prepared to put a range of popular films onto the new discs. This was a major problem because each video disc had to be able to contain a whole film. We then worked on producing a double-sided disc, which made the process extremely critical and expensive. This project was undertaken in California, the centre of the film industry. In the meantime, the video industry was working on developing magnetic tapes capable of holding an entire film on one tape. The sector's 'big guns' had each developed a system they were trying to market.

The race for success depended on the range of films the companies producing them were willing to make available to the three systems. The systems competing with each other were JVC/Matsushita's VHS, Sony's Betamax, and Philips' Video 2000. The outcome would depend on the number of titles available on each system, as this was the crucial factor determining which system consumers would go for. Each system's presence on the various global markets also played a role. The battle was fought out on three continents, in North America (the United States), Asia (Japan) and Europe. VHS and Betamax emerged triumphant thanks to their global presence, whereas Philips only operated in Europe. The success of a newly-launched system depends on the extent and nature of the content available on it, as one amusing detail makes clear.

In the early years it became clear that consumers were very interested in porn films. Japanese companies, taking a pragmatic approach and setting moral scruples aside, had no hesitation in putting this kind of film on their product. This gave them immediate success, which allowed the industry to ramp up quickly and thereby benefit from economies of scale, which soon reduced the cost price of their equipment and therefore market rates.

However, Philips and in particular the Philips family itself as members of Moral Rearmament did not allow such films to appear on their system. The result was that the Japanese systems won out and Philips had to abandon the Video 2000 system. Subsequently, Sony also had to abandon its system. Given the success of the VHD format, and consequently the huge quantities sold across the world, this allowed the Japanese to offer ever lower prices.

LaserVision technology was still in its infancy. The production of discs – which could be double-sided, so that a blockbuster could be included on one side of the disc – was a very complex process. However, it was what consumers were demanding. This meant that only minimal quantities were sold and the prices of the device became less and less competitive compared with VHD systems. This situation led to the slow demise of the LaserVision system.

The search for an innovative technology

In the late 1970s, Philips announced its intention to replace vinyl with a smaller disc using optical scanning. The Dutch company had been working on this since the 1950s, and was now nearing its goal."

At that time, in the late 1970s, in the Audio Division we compiled a document outlining our future strategy for recorded music. We believed that a new medium capable of holding up to 60 minutes of music, enabling direct access to each individual track or item, with no deterioration due to wear and tear or dirt, and offering higher-quality playback, could revolutionise the experience of listening to music. Against this backdrop, in 1977 – led by Lou Ottens, our technical director who had also been responsible in that period for the invention of the Compact Cassette at our facilities in Hasselt (Belgium) – we launched a project aiming to use laser-disc technology to develop a device and a disc that were able to play music to high quality levels. I established a team of four engineers headed by Joop Sinjou and gave them the funds they needed and my full support to develop this device, which was to completely revolutionise the way recorded music was played. With great enthusiasm they set to work drawing on all the existing know-how in our fundamental research laboratories. At this time, only analogue transmission (in the form of sinusoidal signals) could be used for audio signals. One of the requirements we had to address was the need to design a disc which could reproduce on one side all the recordings featured on the two sides of the vinyl records used in those days. This would allow the music industry to put multiple recordings on a single side of the disc without the need for reprogramming. The first disc was pressed, but the density of the analogue data and their configuration made it impossible to go below a diameter of 17 cm. Mr Ottens – having had previous contact with Sony about the Compact Cassette – then met the developers of studio magnetic tape players, who had produced new digital devices to studio-record music. This was a success, paving the way to apply digital coding methods to audio recordings. The development of our disc thus took a whole new twist as we switched from analogue to digital technology. Our experts in this field were based in the United States, but we brought them back ASAP to apply this digital technology to audio recordings for the general public. In the intervening period, the Japanese had not been resting on their laurels. However, despite regarding the laser disc as a highly promising new medium, they continued to focus on analogue technology using 30-cm discs. We therefore urgently needed to step up the pace of our development efforts, knowing that digital signal could allow us to get one hour of playing time onto one side of an 11 cm disc.

Then, at six o'clock one evening in early March 1979, I received a phone call from project manager Joop Sinjou, who asked me to come down to the lab where a handful of researchers were working on the project. To my astonishment, he told me they had done it! With great pride they showed me what they had achieved: we were able to listen to a laser disc onto which they had recorded passages of audio music. And … lo and behold, a new sound came out of this little machine… it worked… We had a brief discussion with the developers and decided in consultation with Mr Ottens to go and demonstrate our invention to the industry in Japan two months later, although we still had to work hard to remove all the crackling sounds that could be heard in the pieces that were played.

The astronomical price of this first prototype made large-scale distribution impossible, so we immediately set up a meeting with Mr Ottens to examine potential changes to the price of the device's components and of the device as a whole.

Mr Ottens asked his developers to give him details of all the key components and the dimensions and weights of each one. Drawing on his experience of component development, he drew up an estimate of how the costs were likely to evolve. An assessment for each component was made based on its weight, and the final calculation suggested that the price would come down by a factor of 10 within the next five years. As it turned out, the long-term price reduction was much more substantial than that. At that time, the audio industry in the United States and Europe had given up producing audio equipment at home. The whole sector was concentrated in the Far East, primarily Japan. This made it absolutely vital for the audio industry to reach a consensus on adopting a single system and to avoid launching multiple systems as was happening with video-recorder systems. Consequently, we opted for an 'open licence' strategy for our patents so that the whole industry could access them without having to pay exorbitant fees. Every industry had access to the licences held by Philips and Sony subject to signing a contract which stipulated the amount to be paid per device produced at its production value. The fee was set at 2% of this value. For discs this came to two US cents per disc.

Convincing the Japanese

With this in mind, we left for Japan two months later with two demo devices and a large delegation to visit the leading Japanese companies (Sony, Matsushita, Sharp, Hitachi) and the Digital Audio Disc Committee (DAD). We were accompanied by a large group of technicians from the DAD, which had been established by the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), the body responsible for industry standardisation in Japan. The idea behind this trip was to reach consensus on the new system to be adopted by the industry.

The delegation we had put together was made up of General Director of Audio Joop Van Tilburg, Technical Director of Audio Lou Ottens, and me as Director of the Hi-Fi and Compact Disc Department and of the Marantz brand. We were accompanied by the head of LaserVision and our project manager, Joop Sinjou, making five of us in all. We flew first class with our equipment secured to two first-class seats, like a CEO on a business trip to Japan, to avoid subjecting it to temperature fluctuations in the hold. The demo model measured 50 cm by 80 cm, plus a frame featuring a mass of circuits and components. Having arrived at the hotel, our engineers worked on getting the devices up and running again: the flight had interfered with the circuits and they had to labour through the night to get them back in working order. At breakfast, they told us that everything was working and that we could start our visits to the various company headquarters.

The first company we visited was Sony. On our arrival we were told that CBS Sony Records President Norio Ohga would be unable to attend because he had been involved in a helicopter crash that had killed one of those on board but from which Mr Ohga had fortunately emerged unscathed. Akio Morita, Sony's big boss and founder, took his place at the meeting.

Sitting by my side in the front row, he listened with fascination to our little disc while at the same time lamenting under his breath that his laboratories had not been the ones to invent this gem. Following this meeting, we gave the same demonstration at major companies such as JVC, Matsushita (Panasonic), Sharp, Toshiba and Pioneer and had a meeting with the group of engineers at the DAD.

When we visited Matsushita, we were received by the 90 year-old founder himself. He had almost lost his voice and had to use microphones to make himself heard. We spent the whole afternoon discussing the future of this project and that of LaserVision technology. Despite his age and frailty, he remained alert and up to date with the latest developments and was highly attentive to our project, which he obviously regarded as promising even though it was competing with those of his own laboratories. As we were leaving after these discussions, in the hallway we ran into Mr Morita again. He had clearly been talking with Matsushita about how the industry in Japan should react to Philips' bombshell. In Japan, all the major companies have their headquarters in Tokyo, meaning that information can be exchanged quickly and efficiently. On the Friday evening, we returned to Europe and learned that Mr Morita had called our country manager in Japan to ask us whether we would consider collaborating on the system's development. Our 'shock-and-awe' strategy had obviously worked, and the way was now open for the collaboration we were seeking.

Back in Eindhoven, we discussed everything with Board of Directors member and head of Audio Cornelis Van der Klugt as well as with the management of Polygram, our record label. Sony was a wise choice as it was the principal shareholder in CBS Sony, giving it access to CBS's impressive back catalogue – a cornerstone of rock and pop music worldwide. We were familiar with Polygram from its top-quality records and outstanding repertoire of classical music. The four companies, Philips, Sony, Polygram and CBS, formed an alliance bringing together the back catalogue of music required to get the system off the ground. This was based on an outstanding and varied selection of music covering the world's leading performers that was sure to meet the needs of the system's first users.

We then ran a series of press conferences around the word for all the media, the daily newspapers, the trade press, the record manufacturers, the critics and the music copyright holders to win them over to our new system. I remember we went to New York to get the Americans on side, as they held most of the cards in the music industry.

At the Plaza Hotel on the city's famed Fifth Avenue, we gave a series of demonstrations over three days, having sent out invitations to a host of interested parties wanting to know more about this new product. Numerous music industry and media players had signed up to attend. Everything went smoothly until the third day, when my technician colleagues began to look very nervous. It turned out that the very high level of humidity of New York in high summer had damaged the discs, meaning that my colleagues only had two left that were still working. Despite this, the demo was a success and we heaved a huge sigh of relief. It was only after the last demo, which went like clockwork, that my colleagues told me about the hitch, which could have cost us dear. These prototype discs were produced on a very small scale and their deterioration as a result of humidity was completely unexpected. After all these demonstrations, those in attendance praised this new product to the skies in the various US media.

An agreement with Sony

We decided to work with Sony, because of its more Western culture and outstanding expertise. Mr Van der Klugt was tasked with negotiating a potential agreement with Sony as our privileged partner and more specifically with the company's President Akio Morita.

Mr Van der Klugt had just been appointed to the Philips Board of Directors, relinquishing his role as the company's top man in Brazil. He was very much a people person and knew all the industry leaders in Brazil. However, as he was not yet acquainted with the Japanese management, he organised a meeting with Mr Morita to make arrangements for our collaboration. For once, a European company had a considerable head start over its Japanese competitors, and Mr Van der Klugt didn't want to squander this advantage by making any tactical errors. For example, ringing Mr Morita would have been a fatal mistake. To get more familiar with the Japanese, he began to learn about Zen philosophy. Instead of calling Mr Morita directly, he used a clever ruse to engineer a meeting with him, so as to avoid being on the defensive and having to make concessions. He arranged with Mr Morita to meet in New York.

Mr Van der Klugt recalls: "We organised an almost chance encounter in New York. Akio Morita still doesn't know this, but my colleagues and I had decided to contact Sony, and I'd been given the task of leading the negotiations. If I'd made a direct offer and asked for something in return, I would have blown all my cards at once. As soon as I showed I needed something, it would have cost me money. So I had to make sure I didn't ask for anything… One Friday morning, my manager in New York rang me to ask if I was ready. Akio Morita was going to have a coffee with him the following Monday. So I flew to New York and on the Monday morning in question, I was chatting with my manager when Mr Morita came into the room. We struck up a conversation straight away as he announced:

- 'I'm exhausted – I've just come back from Brazil.'

- 'What were you doing over there?', I asked.

- 'Well, I went to see my factories and played golf with one of my friends at the São Paolo club where I'm a member.'

- 'Ah, that must've been Manubu Mabe3', I said.

This allowed Mr. Van der Klugt to avoid the almost obligatory jostling for position with the Sony President and break the ice before launching into a discussion about the standardisation of the Compact Disc. "

Mr Van der Klugt and Mr Morita met on various other occasions in the months that followed, but that first meeting turned out to be crucial as Philips was then able to send a technical delegation to Japan to present its new technology and seek a partnership.

How to get a standard adopted by the whole industry

A race against the clock then started as we worked with Sony, Polygram and CBS Sony engineers to decide on the various features of the new system. Properties such as the disc design, the number of bits to format, the playing of the disc from the centre to the edge, the number of bits to use for the music and the number to use for extra information such as titles, the texts used in the booklets, the number of revolutions per minute and so on had to be agreed with the various groups of engineers.

Among the key issues addressed during discussions, it was decided to change the device's capacity from Philips' favoured 14 bits to the 16 bits preferred by Sony, holding out the prospect of one day combining images and audio.

A fixed schedule was worked out for exchanging data between the various laboratories, alternating between Japan and Eindhoven. Regular progress reports had to be submitted to the DAD in Tokyo.

Three rival systems were studied by the DAD group: Philips Sony's Compact Disc, Telefunken's Teldec, and the JVC system.

To get the decision to come out in our favour, we had to persuade JVC to abandon its system. Leading these negotiations, Mr Van Tilburg gave Matsushita/JVC access to the system without having to pay royalties5 on the device and thereby secured an agreement.

When Matsushita sided with Philips/Sony, the DAD's entire group of engineers, which had to choose just one system, lost no time in making what had become an easy decision. The JVC system and Telefunken's Teldec system were dropped and consigned to the archives.

We had regular meetings with Sony led by CBS Sony Records President Mr Ohga. At one of these meetings, he showed me a small portable compact device he used to listen to music on planes.

Mr Ohga was a real music lover. While studying in Germany at Mr Morita's request, he married a leading pianist. It was during his time there that he became friends with Herbert von Karajan, who would later do so much to promote the new Compact Disc system among artists.

The little device in Mr Ohga's luggage was the first Walkman. Mr Ohga travelled a lot and would have liked to listen to his favourite songs on the plane. When in the laboratories there were 50,000 Dictaphone units which just could not be sold, he asked his developers to transform one of them into a Compact Cassette player with a long battery life to be able to listen to music during his flights. As President of CBS Sony in Japan he needed to go to the United States on a regular basis to visit CBS in New York, meaning that he travelled a lot. This led him to invent the first Walkman. He demonstrated this device at one of our meetings.

I called one of my colleagues, who was in charge of portable audio devices. He listened to it but when he saw the device was going to cost 450 Dutch guilders (€190), he thought it would be impossible to sell it in bulk. Of course, subsequent events proved him completely wrong. Whenever I met Mr Ohga on my visits to Tokyo, he would proudly tell me that Walkman production was rising at a rate of 10,000 units a month, initially to 25,000 and then to 50,000 – a stunning success which he positively glowed about.

Given the progress of the CD project and the need to have Polygram under Philips' full control, Mr Van der Klugt decided to shake things up at Polygram by acquiring Siemens' 50% stake in the company. At the time, Polygram was in real difficulty and only had a 6% stake remaining in its own equity. As a result, there was strong resistance to any investments in new systems such as the Compact Disc. To have free rein in this regard, Mr Van der Klugt decided to acquire Siemens' shareholding in order to take control of investments so that all the necessary funds could be pumped into developing the Compact Disc and the Hanover plant where the discs were to be manufactured. This move didn't cost a huge amount because the company, like the rest of the music industry, was in dire straits financially, meaning that Philips was able to acquire the whole organisation for a pittance. Having this record label under Philips' complete control meant that Mr Van der Klugt could restructure Polygram's operations to give the company the boost it needed.

He replaced Polygram's management, with the flamboyant Jan Timmer – who would later become CEO of Philips – taking the helm there.

While the group in charge of developing a standard was gathering momentum in 1980, Mr Van der Klugt was already thinking about the next phase of introducing the new system. If Philips didn't manage to convince the record companies to adopt the new Compact Disc, no discs would find their way onto the optical scanner and it would soon be forgotten about. However, it seemed it would be impossible to convince the five biggest companies in this sector, CBS, Warner, WEA, RCA and EMI. The record industry has little interest in change, and had even less in the early 1980s. At that time, the whole industry was caught in a dangerous downward spiral.

One Saturday morning, when Mr Van der Klugt was getting ready to play golf, he received an anxious phone call from Mr Morita in Tokyo. From Walter Yetnikoff, the President of CBS Records, who was producing records in Japan under an agreement with Sony, Mr Morita had heard about a meeting that was planned in New York the following week, bringing together the bosses of all the major US record labels.

His problem wasn't knowing whether they were going to discuss the Compact Disc but rather whether they were meeting so that they didn't have to talk about it at all. Mr Morita, who by this stage had invested vast sums in the project, was concerned about the whole thing being put on ice and feared that after reaching an informal agreement, the record companies would allow this elaborate technology to be lost through mere negligence.

If these companies, which controlled more than three quarters of the industry, had publicly made an agreement to reject getting involved at all in the Compact Disc venture, this would have represented a boycott breaching the antitrust legislation in force at the time in the United States. But there were of course ways of meeting, discussing things in a cordial atmosphere and making common cause, although nobody had ever talked about concerted action. This is what Mr Morita, informed by his business partner Mr Yetnikoff, explained to Mr Van der Klugt.

The main bone of contention was the licence fee Sony and Philips were seeking from the other Compact Disc manufacturers. While this was only three US dollar cents per disc for a product whose retail price often came to more than twenty dollars, if we sold millions of records a year, Philips and Sony would have made a small fortune out of it.

That morning, Mr Morita suggested to Mr Van der Klugt that the patent holders should waive this fee.

Mr Morita wanted Mr Ohga to go to New York and asked Mr Van der Klugt to do the same. Mr Morita told him: "If you don't do the same as me, the newspapers will say you're responsible for this failure." Mr Van der Klugt replied by asking Mr Morita to calm down and to give him 24 hours to think about it, saying: "Don't get involved in this. We'll take care of everything." Mr Morita protested and then hung up.

Mr Morita immediately called the CEO of Philips, Wisse Dekker. He in turn immediately rang Mr Van der Klugt to ask him what he was planning to do to circumvent this wall being set up to block the Compact Disc. After a tense discussion between Mr Van der Klugt and Mr Dekker, Mr Dekker gave Mr Van der Klugt the go-ahead and asked him to get things moving. Mr Van der Klugt called Mr Morita and asked him to waive the right to his three-dollar cents but didn't tell him how he would go about it. After several more conversations, Mr Van der Klugt finally revealed his hand to Mr Morita, but not before it was too late for the latter to intervene. This involved Polygram – accompanied by two lawyers – joining in the New York meeting, with anybody make any reference to a boycott facing the prospect of arrest on leaving the room, given that in the United States, deciding on a boycott would have been a criminal act.

The marketing of the new Compact Disc product

The time had now come to give the new little disc a name. My head of advertising took it upon himself to draw up a list of names. There were 50 of these. To decide between them, Mr Ottens, myself and Mr van Tilburg met one evening in the latter's office. From this long list of options we agreed on the name 'Compact Disc'. This was an obvious choice as it created continuity with the Compact Cassette, another product invented by Philips which had spread around the world. Our designers devised a logo which was then passed on to Sony, who accepted it and agreed to use it in every country on all CDs. This consent was laid down in a grant of official recognition of the legal name.

I also instructed my staff to draw up a marketing plan. The primary goal was to properly position the product. A clear and succinct sales pitch was developed to position the new device among the existing products for music reproduction. This went as follows:

- The Compact Disc had an unprecedented reproduction quality ranging from 20 to 20,000 Hz.

- Its signal was unchangeable.

- It could switch immediately from a weak to a strong signal.

- There was instant access to the data on the disc.

- Damage to the disc from scratches or other sources couldn't be heard.

- The playtime for one side of the disc was one hour (as we will see below, this would later be extended).

- The case design enabled disc titles to be read easily in a record library.

The disc was a thing of dazzling beauty. I instructed everyone demonstrating the new product to drive home these arguments, so that the product would immediately be associated with all these benefits.

Polygram's industrial and marketing plan

Mr Timmer then swiftly made some vital decisions. He put Hans Gout, a marketing expert at Polygram and formerly a marketing specialist at Unilever, in charge of all marketing for the disc.

For the industrial side of things, he asked Siemens engineer Hermann Franz to come up with a plan for launching CD production at the Langenhagen factory in Hanover.

Langenhagen was chosen because it was the Group's best-performing factory in terms of quality. Moreover, it was in Schleswig-Holstein, a German region renowned for its high-precision workforce.

Under a 500-day programme, the factory would be transformed into an environment similar to those found in the chip industry, i.e. involving completely dust-free enclosed areas. The presses were developed in Aarburg, Switzerland, by specialists in high-precision presses.

We held regular meetings, at which the discipline of Dr Franz's team became apparent: they adhered rigorously to the 500-day timetable. For his part, Mr Gout really took the bull by the horns.

The Compact Disc's design was originally determined by legal requirements regarding the disc's appearance. Vinyl records had a label in the middle on which the contents of the record, the composer and the performers were printed, as laid down by legal rules on copyright and performers' rights. Transferred to Compact Discs, this would have meant a tiny label 4 cm across in the middle of the disc, which would have been impossible for consumers to read. These legal agreements therefore needed to be overhauled.

Mr Gout, with his marketing flair, completely changed this appearance, allowing the whole of one side to be used for information about the contents of the disc, the composer, performer, and so on. Furthermore, the whole surface could be used for artistic purposes as background decoration.

This was immediately greeted with great enthusiasm – including by industry players, who saw this decorative layer as providing additional protection for the data contained on the disc.

The second major innovation was the packaging. Vinyl records came in cardboard sleeves which were difficult to identify in a record library. Mr Gout and his designers came up with a brand-new form of packaging. Below an example of a disc in simple packaging with black plastic support for transatlantic shipments.And an example of an album featuring several discs (e.g. for an opera).

A small plastic case whose spine could be used for information about the disc's contents was put forward, meaning that the details on the spine could be read when the disc was stored in a record library. Inside was a very flat plastic support on which the disc could be mounted. Incorporating this into the case gave the whole thing a classy look. It was also possible to place little booklets inside the case, including the lyrics of the songs and operas featured on the discs, as well as information about the composer, orchestra or performer.

He later invented double- and multiple-CD boxes for works requiring multiple discs, such as operas.

The purpose of the plastic support, securing the disc to a very flat surface, was to minimise the size of a stack of 50 discs. Initially these discs had to travel across continents as there were only two factories producing the Compact Disc: one in Hanover and the other in Tokyo.

Mr Gout had planned an extensive series of behind-the-scenes demonstrations for artists and music specialists. A major presentation was organised at the Salzburg Music Festival at Easter 1981 to show the public and music lovers the excellent sound quality provided by the Compact Disc.

Polygram's star conductor Herbert von Karajan, a great friend of Mr Ohga, was one of the first to hear the new invention. He was so charmed by the clarity of the sound that he became a keen advocate of the CD, promoting it with an enthusiasm quite rare among musicians.

Mr Timmer and Mr Gout had focused their plan on the Compact Disc's excellent sound quality. The industry's prevarications would not stop us pressing ahead, backed up by 23 powerful record companies in Europe and Japan.

Mr von Karajan played a key role one Wednesday, the customary rest day for the Salzbourg Festival, when classical-music critics leave the concert halls to meet the world's top musicians. To win them over, he invited them to a concert hall and spent the whole day demonstrating the Compact Disc.

At these meetings, Philips and Sony gave a bravura demonstration of the music's sound quality. Having taken the floor, Mr Morita managed to get the audience on side by having the disc gleaming in his hand, lit up by powerful projectors which reflected this light throughout the hall.

The Compact Disc glittered like a jewel, increasing people's fascination for this new, top-quality product.

The effect on musicians was decisive. They asked to have their works put on this new disc as soon as possible. And so the ball got rolling.

A series of demonstrations around the world at all the international fairs only further whetted the appetite for the introduction of this new musical medium. At Philips' Annual General Meeting in Ouchy (Switzerland) bringing together all of Philips' national management teams, I had the task of presenting the product to them and telling them about the launch plan.

This was greeted with universal astonishment and enthusiasm. The marketing teams were responsible for devising launch plans in conjunction with the Polygram entities in their countries.

Finalization of standards

We were coming to the final phase of negotiations on the various standards. The last meeting to decide on all the technical standards, as well as the distribution of royalties between Philips and Sony, was held in Eindhoven.

At the start of the discussions, Mr Ohga broached a completely new subject: he turned to me and asked me to kindly consider a very specific request from Sony, namely his suggestion of increasing the disc's diameter which had been set at 11.5- 12 cm. We were completely baffled by this as we had chosen the 11.5-cm diameter after careful thought. This was also the diameter of the Compact Cassette, and it had proved to be an excellent choice as it enabled devices to be created in all applications, ranging from the cassette recorder and ghetto blaster to the Hi-Fi system and all types of car radios.

Indeed, the size of space provided for car radios is laid down by DIN standards, which the whole industry adheres to. The development process for new car models takes almost five years. It was therefore absolutely vital to have a Compact Disc format that could be integrated into all these applications.

I replied to him that we had chosen a size which took into account all these fields of application.

Mr Ohga's answer was rather disconcerting. He told me: "In our homes at Christmas, we usually play Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. This symphony conducted by my great friend Herbert von Karajan lasts 76.5 minutes and so could be played continuously on one side."

I responded: "A 12-cm diameter would compromise the flexibility of the applications in all devices, as with the Compact Cassette."

He retorted: "My engineers have checked all of that and a device for cars can meet the dimensions laid down by the DIN standards while easily fitting into the spaces provided in cars by automotive manufacturers."

With this knock-out argument, he won everyone over.

The diameter was set at 12 cm, which remained an optimal size for all subsequent applications, such as the DVD.

The royalties were shared between Philips and Sony, with Philips receiving 75% and Sony 25%, reflecting the weighting of the two companies' licences and therefore their contribution to the development efforts. Most of these licences lasted until 2002.

Product launch

In consultation with Sony, we decided to launch the product at the Tokyo trade show in September 1982.

At the introductory presentation at this event, 17 firms showed models, all of which had front loading.

Preparations were well under way at our Hasselt facilities for the production of the CD player, and in our Hanover factory for the discs. In August, four presses were installed and up and running. A huge hall allowed for all these units to be expanded, with zero dust generation. A battery of magnificent Swiss-made presses was lined up in this huge hall.

The first model of the device was designed by our design centre in Hasselt under the supervision of Hugo Vananderoye, a rather headstrong man who was proud of the models he had designed for the cassette. His design for the CD player had a door opening on top of the device. This made the device very compact but meant that it didn't fit into Hi-Fi systems, which had standard dimensions and were loaded from the front.

As development was a slow process in Europe and any design modifications would have caused a delay, it was too late for us to make any changes, so there was no time left to develop the front-loading model.

In June 1982, Dr Franz kept his promise as a series of perfectly formed discs rolled off his production line. This first series of discs – 300,000 of them in all with a back catalogue of 150 titles, most of them classical music – was sent to Japan to launch the Compact Disc at the Tokyo Hi-Fi Show that September. Philips was also producing Compact Discs in Hasselt in anticipation of their European launch in the spring.

Mr Timmer observed that something very special was happening, with the Compact Disc being welcomed by classical-music lovers, rock-'n'-roll fans and old-time jazz enthusiasts alike.

Millionaire:

“The first commercially produced CDs, coming out of Hanover on 17 August 1982, were ABBA's The Visitors and Richard Strauss's An Alpine Symphony, directed by none other than... Herbert von Karajan! However, the first CD to sell more than a million copies was the album Brothers in Arms by the US group Dire Straits, released in 1985.”

This popularity was in fact terrifying as only the Hanover and Tokyo factories had started manufacturing discs. We were soon experiencing stock shortages, which hampered the continued expansion of the new product.

The system's introduction in Europe further exacerbated the huge demand for discs among the new owners of CD players. This made it absolutely vital to increase production and persuade other companies to invest in this new Eldorado of the music industry.

As the US market had the most potential, the launch there was delayed for as long as possible to avoid further fuelling the demand for discs, given that such demand couldn't be met.

Production in Hasselt started slowly, and we faced various problems. One of them was that our models were less tailored to the market, and the other was the delay we were experiencing in developing less expensive, new-generation models. My technical director Gaston Bastiaens, who was in charge of all technical, development and production problems, tackled the latter issue head on. He brought together a series of experts from the company and pooled all of Philips' in-house knowledge in order to resolve the delay.

Philips encountered further difficulties in expanding the Hasselt facilities, which had to multiply their planned production capacity several times over in their first year of operation. But that wasn't the biggest problem Mr Bastiaens faced. In early 1983 he travelled to Japan, where he noticed that Japanese manufacturers were already 18 months ahead of the game in terms of the development of new types of laser, integrated circuits and motors, as well as new machinery that cost less and was better designed.

Making a quick calculation, Mr Bastiaens estimated that three years down the line, a Japanese Compact Disc that cost €400 on the first day of production would only cost €120 and would be of much higher quality. By contrast, at the forecast growth rate at Philips, he calculated that it would take five years to achieve the same outcome. But by then the market would have abandoned Philips to return to more familiar ground, namely Japan. Philips would then become merely an accessory in an industry it had created. As a result, Mr Bastiaens raised the alarm. The only solution was to break with Philips tradition by ending the era of informal knowledge sharing and introducing a more 'military' Japanese-style enterprise. He convened a meeting of 90 people, bringing together engineers, designers and manufacturing specialists, and asked them to think about ways of improving the quality of Compact Discs while reducing their costs.

Following the meeting, small groups were set up, to start thinking about how to completely restructure the CD-player assembly process.

These groups generated many new ideas, which were discussed and adopted at quarterly meetings.

One striking example is that of the laser beam, which reads the disc's cavities. In 1983, it was made up of 17 components, with materials and labour costing a total of €50. Four years later, it had just six components and cost €12. In four years, the price of the various components of a CD player fell from €400 to €125. This allowed Philips to gain an edge over the competition.

The success of the new golden rule introduced in Hasselt can be clearly seen in the figures for 1986, when around 1 billion CD players were sold worldwide. Three of the top five producers, Sony, Matsushita and Philips, together accounted for one fifth of this total.

On the marketing side, I got all our country entities to devise marketing plans and take on a dominant market position from the start.

There was a large-scale promotion plan. In agreement with Mr Timmer, we teamed up with top rock band Dire Straits and its lead guitarist Mark Knopfler, and planned 250 concerts with them worldwide. To manage this project, I picked a young Hungarian, Stéphane Somsich, who could speak several languages including Japanese, having spent a number of years in Japan. The band travelled from city to city around the globe, together with a host of technical assistants to ensure top quality and seamless organisation wherever they performed. The band and its entourage consisted of 50 people travelling by plane or truck. The whole project cost 10 million Dutch guilders (€4.5 million).

This tour was a phenomenal success. At every concert it was obvious that music fans were won over by our Compact Disc.

The figures at the end of 1983 made good reading for Philips. Despite a repertoire of just 1,000 titles, the success of the new product amazed both us and the industry.

Phenomenal

“From then on, the CD's popularity continued to grow. The public was won over by the quality of the music and by the fact that the CD, with no direct contact between the disc and its reader, deteriorated little if at all over time. In 1986, sales of CD players were already outstripping those of record players, and in 1988, the CD became the best-selling medium for playing music. In 25 years, more than 200 billion CDs of all types have been sold – a staggering figure."

At the introductory presentation at the Tokyo trade show, 17 companies demonstrated a model. From the outset, all the companies showed off a model with front loading.

Back in Eindhoven after the Tokyo show, I called an urgent meeting with the Development team, and instructed them to come up with a front-loading model as soon as possible.

At the same time a race to create cheaper models was under way. Thanks to rapid developments in Japan, prices were falling fast and we knew we had to develop a flat and inexpensive frame as quickly as we could.

A year later, we introduced the Compact Disc in the United States. This was backed up by a new disc factory, which meant there was sufficient capacity to supply the US market.

Thus the Compact Disc was born, providing employment for thousands of people worldwide.

Polygram became a flagship subsidiary for Philips, amassing huge profits. Given the growth in production of CD players, demand for the disc significantly exceeded supply.

These devices, like any electronic device, were launched in a frantic rush in terms of production volumes, with tremendous pressure on prices. There was fierce competition and, as with all component-filled electronic devices, a race began for mass production at the lowest possible price.

For Polygram, however, the outlook was much rosier. Mr Timmer kept the prices high, made huge margins on his products and led the market with a substantial production capacity, allowing him to press discs for every record label.

The Compact Disc: digital music’s first success

The hugely successful Compact Disc, which dominated the world of music for almost 30 years, found itself competing with new applications. The MP3 standard was created, which gave rise to music distributed on the internet. People could now listen to music anywhere: using headphones, a docker, or other music systems.

This move to MP3 and its successors allowed Apple to introduce the digital system. To avoid copyright issues, Apple came up with iTunes, which limited illegal copying of music on the internet. Music could now be distributed using this technology on all media.

Another development was the CD-ROM, for which my laboratories also laid down the standards in a booklet dubbed the 'Yellow Book'. This application replaced cassettes in all computers and remains a common feature of computers to this day.

The DVD – the video application of the Compact Disc – was made possible thanks to the vast capacity of digital technology, allowing users to store feature films on one side of this little disc.

All these applications show the key role the Compact Disc has played in the spread of music and video into every home and every new personal device. Polygram experienced a golden age. By keeping the prices high of Compact Discs high and selling them in huge quantities, the company amassed enormous profits.

The CD was a gold mine, with sales peaking a few years later. Polygram was sold to Canadian firm Seagram for a record 10 billion guilders (€4.25 billion).

The Compact Disc and all its derivative products had generated massive profits for Philips.

My friend Mr Timmer went on to become the CEO of the global Philips Group.

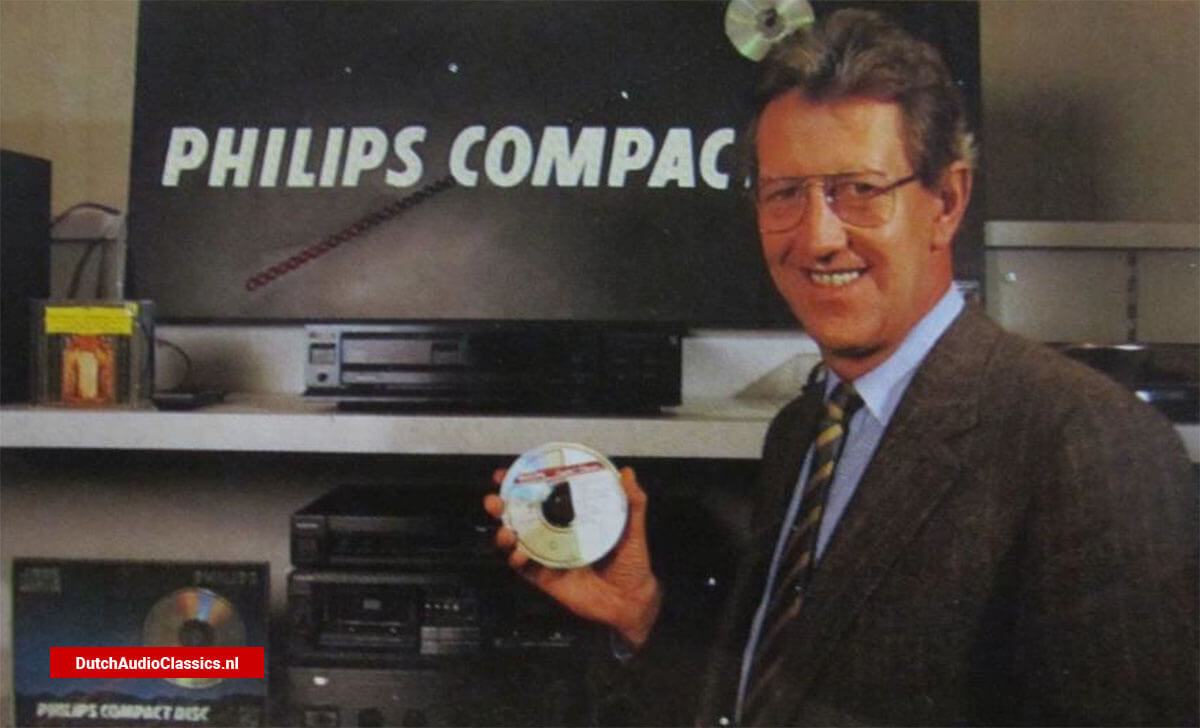

As director of division Audio at Philips in Eindhoven (the Netherlands) in the seventies/eighties

As director of division Audio at Philips in Eindhoven (the Netherlands) in the seventies/eighties

The certificate recognising a major invention awarded by The Mainichi Newspaper, which Francois Dierckx received in Japan for the invention of the Compact Disc and the project revolving around it. The first time the honour had ever been bestowed on a foreigner.

The certificate recognising a major invention awarded by The Mainichi Newspaper, which Francois Dierckx received in Japan for the invention of the Compact Disc and the project revolving around it. The first time the honour had ever been bestowed on a foreigner.

English traduction of the Mainichi certificate.

English traduction of the Mainichi certificate.