The Japan Audio Fair in Tokyo and the Audio Engineering Society Convention in New York reliably forecast the Winter CES.

In this issue we come on like high fidelity gurus, predicting what will be wowing you later this year, even though we had to write about the new goodies before they were unveiled at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. Pretty spunky of us, you say? Nonsense! Our secret is that the major trends were laid out before us the preceding fall at a pair of industry events, making prediction a snap. Of course, a lot of specifics will be revealed only in Las Vegas (and our April issue will be full of them). But as far as the major thrusts are concerned, there is little room for an upset in the stretch, because the industry must actually work years ahead of itself if marketable products are to be ready on time.

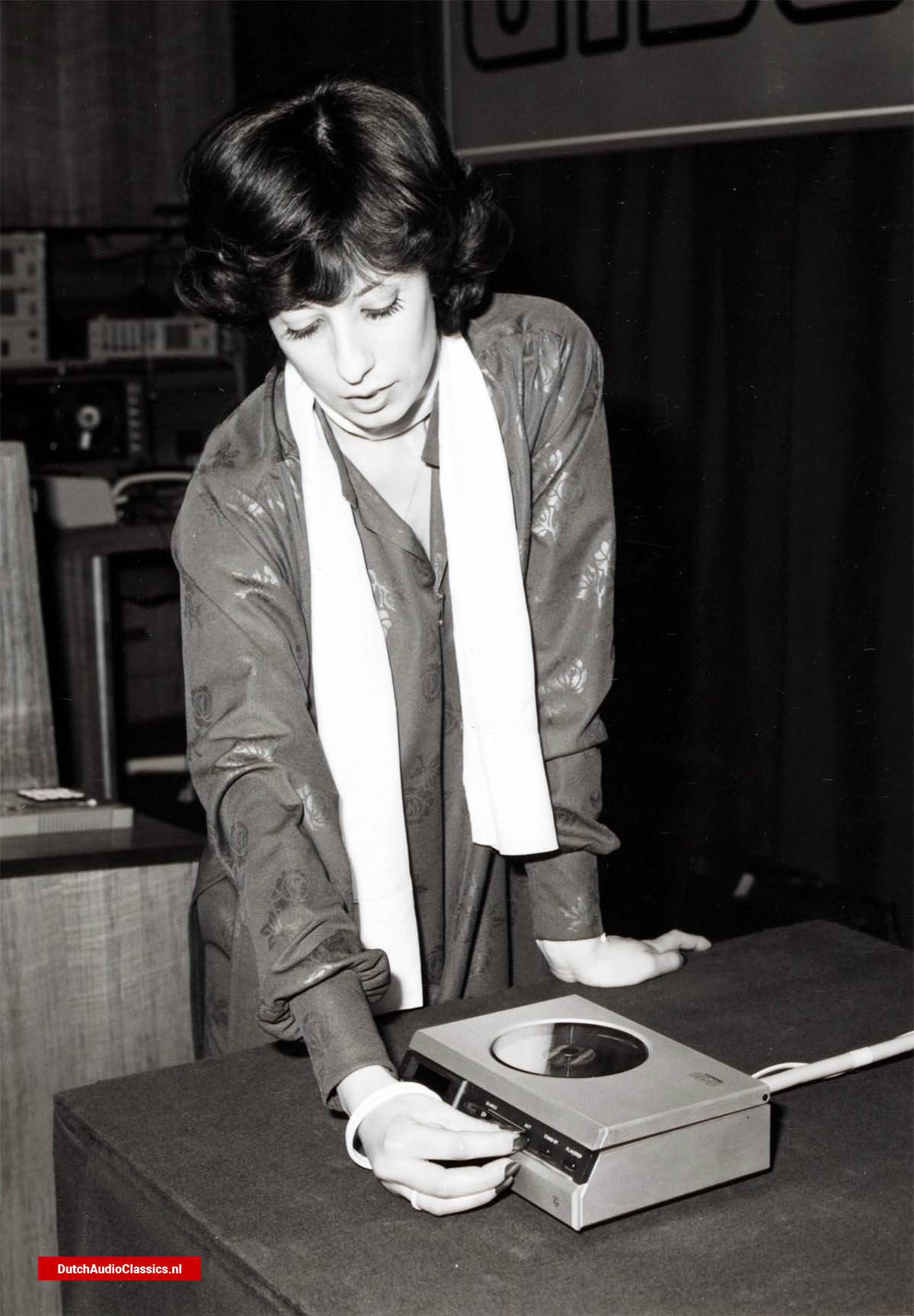

![Philips Pinkeltje prototype demonstration 1979]()

Take the matter of digital audio. The pace of "capability demonstrations" and prototype unveilings has been picking up in the last year or two, and the Japan Audio Fair last October made it plain that the pressure for early adoption of a digital -disc standard has increased radically. In 1980, an important segment of Sony's exhibit was given over to the demonstration of prototype compact discs-the Philips laser -read digital format-while Pioneer showed a

similar but incompatible format, also in prototype. In 1981, Pioneer joined Sony with a prototype Philips -format player, and so did many other companies.

So commonplace were the players, in fact, that the gossip at the Japan Audio Fair centered not on which companies were "in the club," but rather on which were far enough advanced with their prototypes (and, in some cases, with their in-house integrated -circuit production) to get all the necessary electronics into the prototype. Some who lacked the ICs (and therefore the space) relied on outboard digital -to -analog converters tucked out of sight during the demonstrations; others proudly explained that they already could produce a self-contained player. The difference is in time rather than technology, of course; the have-nots can catch up soon enough since many suppliers are at work on the necessary ICs.

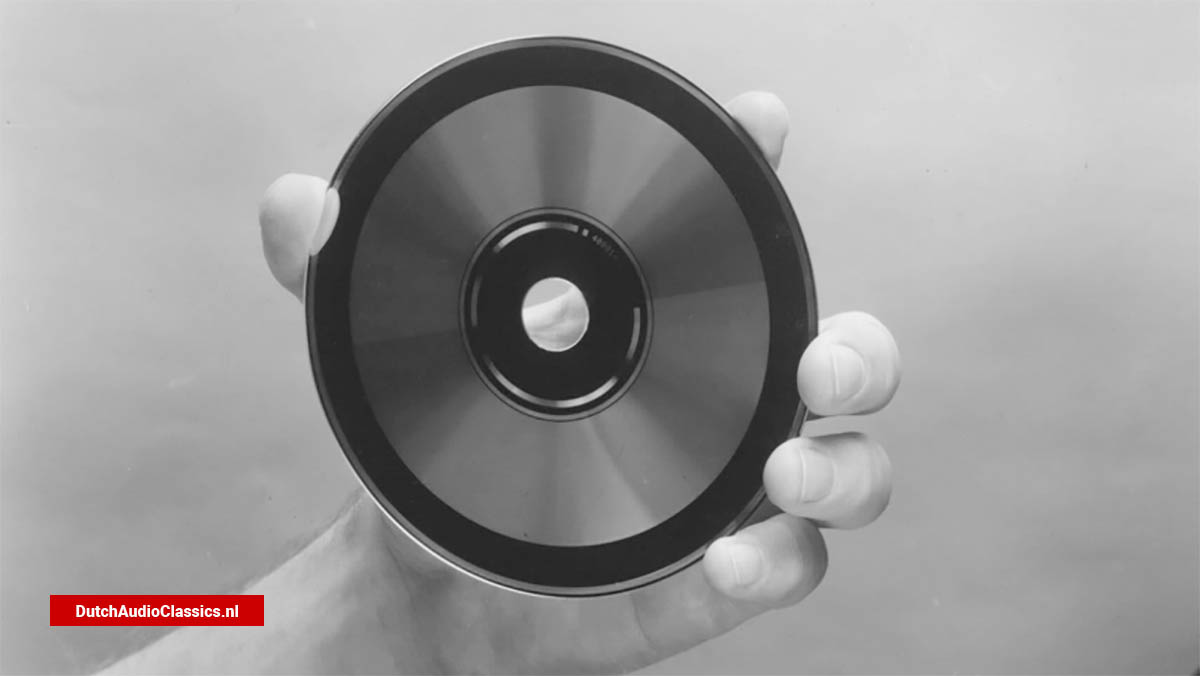

Because this digital revolutionimpressive though it is-is not yet in production or even scheduled for production, it is subject to almost instantaneous change. Though the preponderance of the digital - disc prototypes in Tokyo followed Philips' lead, JVC's AHD format is there for anyone who wants to adopt it, and the conversion from one format to the other conceivably could overtake the industry at any moment. For the present, then, the point is not the format, but the fact of digital audio discs as a concept whose time appears to be imminent.

![Compact disc]()

So it appears reasonably certain that by the time you read this we will have witnessed a new round of digital -disc demonstrations, with the emphasis on the Philips- style compact disc, as attention -getters, but with introduction dates and prices yet to be announced. What was out of reach in 1981 is just out of reach this year.

A little farther beyond the consumer's grasp, but also moving closer, is a digital compact cassette. Until last year, digital audio tape systems generally relied either on open reels or on video cassettes to supply the tape itself. In Tokyo, and at the Audio Engineering Society Convention in this country in November, several companies came out with prototype decks in which the tape is essentially a regular audio cassette-usually loaded with metal tape. Transport speeds, track formats, and encoding patterns differ from one company to another (at least for the present), but all share a common thrust. In fact, the specifics of any given system can be quite volatile; the message is not how far along any company happens to be at any given moment, but that each has committed serious engineering effort to the development of a compact digital cassette.

In a way, digital audio is the logical extension of the many microprocessor - based functions that have been appearing in componentry in the last few years. The trend continues, and based on what I saw in Tokyo I'd say we're entering a sort of second -generation microprocessor binge. The first round introduced rank upon rank of little pushbuttons-particularly in cassette decks, where various random-access systems were created by the microprocessor chips. The new wave, if I may call it that, goes in for flush squares and rectangles and applies microprocessors in less obvious ways. Digital volume controls are beginning to appear, for example, and may well become as commonplace as digital tuning circuits now are. Touchplate controls similarly seem to be catching the attention of more and more companies.

As a result, the round knobs and heavily sculpted aluminum faceplates that have dominated electronics-particularly re- ceivers-in recent years may well begin to look a little dowdy compared to the brisk, crisp styling that some companies will have shown in Las Vegas by the time you read this, though traditionalists who avoid what might be called "industrial" styling should have no difficulty satisfying their needs, in moderate -price equipment.

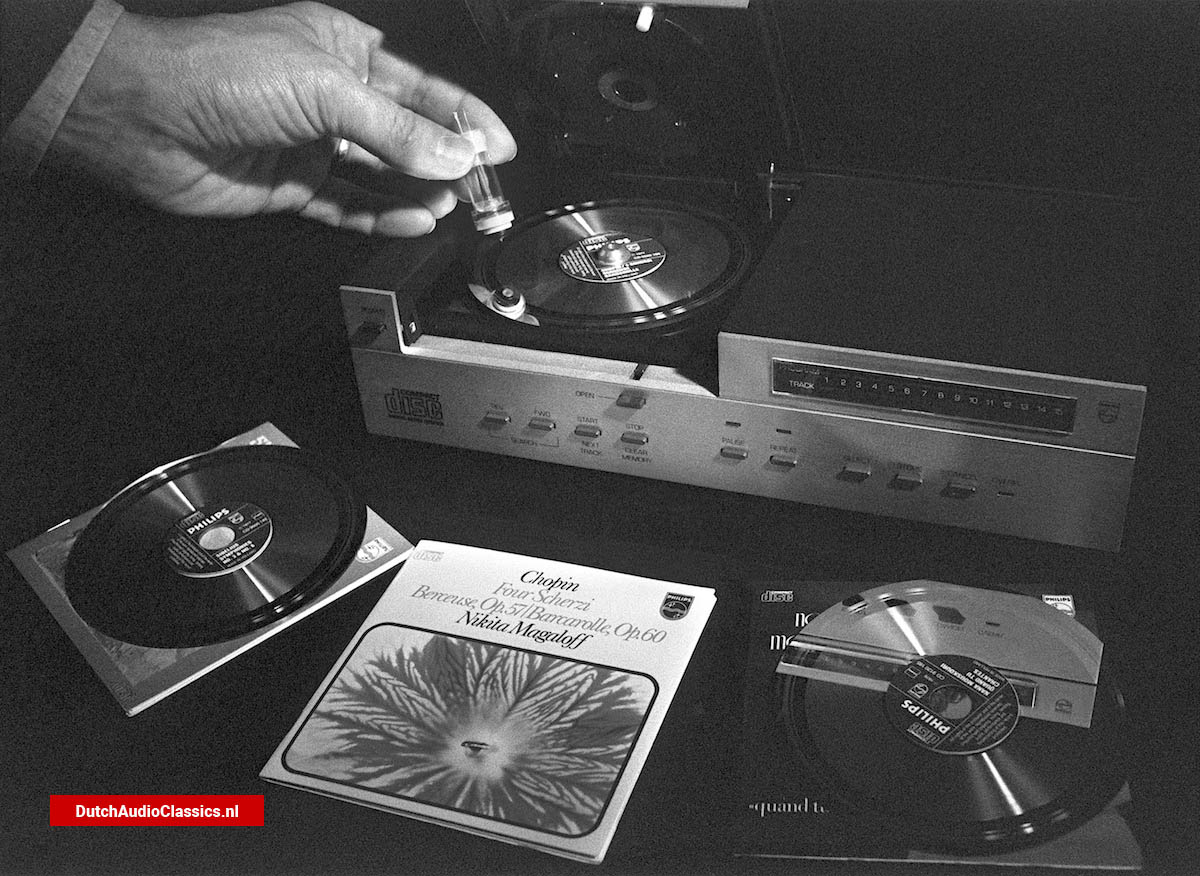

![Philips demonstration model]()

Performance factors in electronics continue to be enhanced by "supercircuits" (including those built into ICs) of one sort or another, though their effect may seem less obvious than that of the convenience features to the average music lover. In turntables, there are a number of new super - hefty models whose sheer bulk helps to isolate and refine the act of tracing the record groove. Of these, the most original, perhaps, is the Nakamichi entry (detailed in the product preview on page 37), which senses and corrects for record eccentricity. And loudspeaker designers continue to exert their ingenuity in search of the ideal flat - diaphragm driver, among other things.

But a sense of the imminence of digital audio colors much of what is being done and said among audio manufacturers, as witness the Tokyo show and the New York convention. And that is certain to be true in Las Vegas, as well.