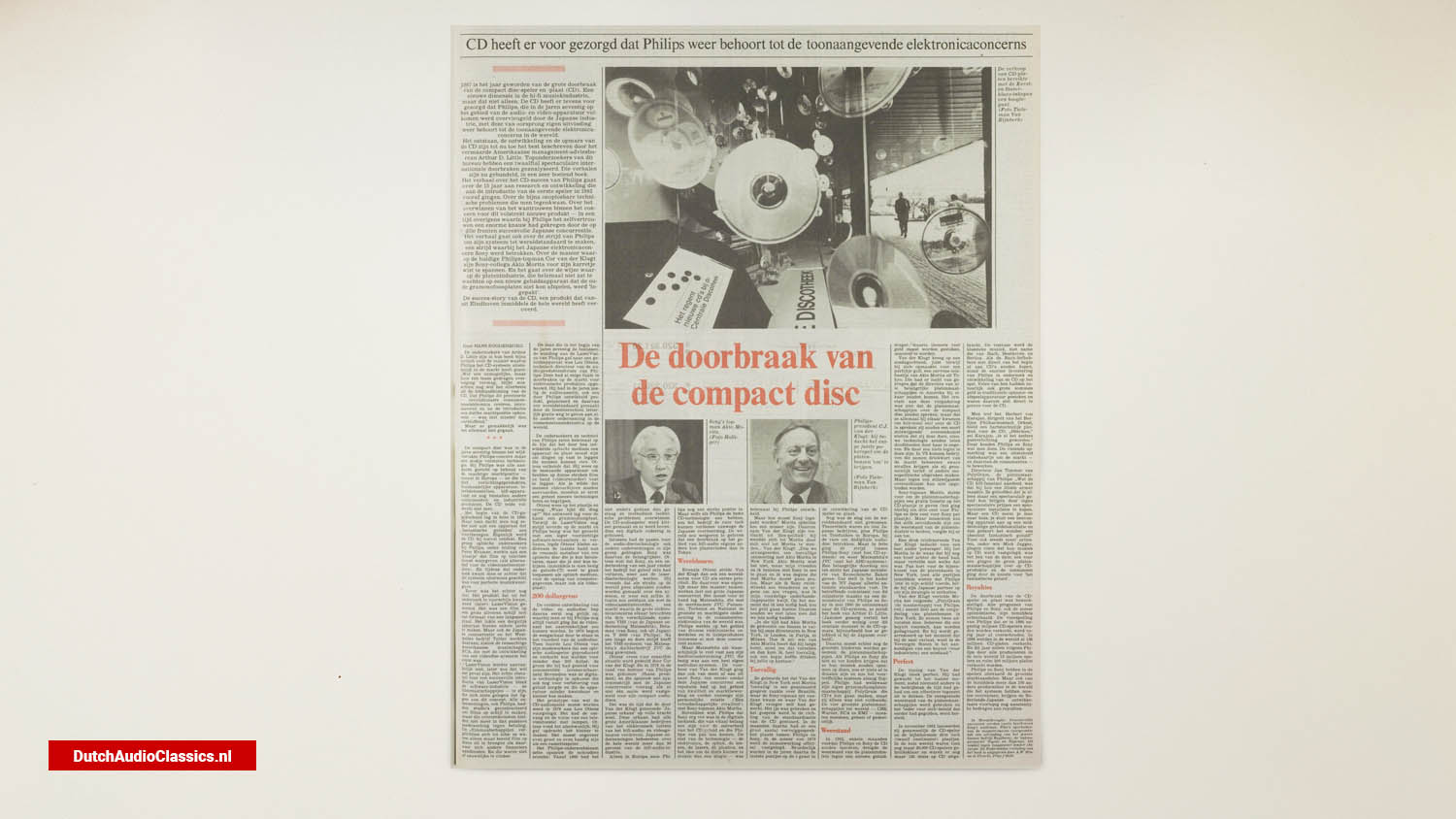

1987 became the year of the great breakthrough of the compact disc player and record (CD). A new dimension in the hi-fi music industry, but not only that. The CD also ensured that Philips, which was completely outstripped in the 1970s in the field of audio and video equipment by the Japanese industry, was once again among the world's leading electronics concerns with this invention of its own origin.

The origins, development and rise of the CD have so far been best described by the renowned American management consulting firm Arthur D. Little. Top researchers from this firm have analyzed a dozen spectacular inter-national breakthroughs. Those stories have now been compiled, in a highly engaging book.

The story of Philips' CD success covers the 15 years of research and development that preceded the introduction of the first player in 1982. About the almost insoluble technical problems encountered. About overcoming the distrust within the group for this completely new product - at a time when Philips' self-confidence had been shaken by the Japanese competition, which was successful on all fronts.

The story also tells of Philips' struggle to make its system the world standard, a struggle in which the Japanese electronics group Sony was involved. About the way in which current Philips top executive Cor van der Klugt managed to pull his Sony colleague Akio Morita into his stride. And it is about the way in which the record industry, which was not at all waiting for a new sound device that could not play the old records, was 'wrapped up'.

The success-story of the CD, a product that has now conquered the entire world from Eindhoven. In their book, Arthur D. Little's researchers are almost lyrical about the way Philips eventually marketed the CD system: What an impossible, but team-based conviction. This is perhaps best demonstrated by the creation of the CD.

"That Philips managed to create and introduce a revolutionary consumer electronics system and build a strong market position after its introduction was nothing short of astonishing." But all had not gone so easily. In the Seventies within the widespread Philips group was just a piece of outcast technology. At Philips, all attention was focused on maintaining its powerful market position especially in Europe - and that covered lighting products, household appliances, television sets, hi-fi equipment and dozens more consumer and industrial products. The CD did not count at all. In fact, the beginning of CD history was in 1968. But back then, people were certainly not thinking of a device that would produce "fantastic sounds."

In fact, the CD was discovered by accident. A group of optical researchers at Philips, led by Peter Kramer, was working on a "picture" that would reproduce film on television (as an alternative to the videocassette recorders). And during that research they found out that this system was extremely suitable for perfect music reproduction.

However, this was not yet the case. The product that emerged from the research was (later) called LaserVision. It was a film on a large silver disc the size of a long-playing record. It managed to make such a device within a few years. But Japanese competitors and the West German company Teldec also worked on it, as well as the giant American company RCA, which was the furthest along in developing a videodisc system. LaserVision did not work at first; later it would. The real obstacle to the successful introduction of LaserVision turned out to be the software industry and the film companies, which did not care about this concept. All of the companies, including Philips, had contracted studios to make films on film, but these agreements involved nothing more than passive cooperation in return for payment.

The film companies committed themselves to nothing: they were only willing to release films on discs if other financiers presented themselves. And they were few and far between. The man who made the decisive turn from Philips' LaserVision to a sound device in the early eventig years was Lou Ottens, technical director of Philips' audio products division. This one had already established some fame in breakthroughs on the market for electronic products. He had launched the audio cassette, also a Philips-developed product, in the 1960s and made it a world standard by giving away the licensing rights literally for free to every other consumer electronics company in the world.

Philips' researchers and engineers were completely in agreement that the optical medium and device and plate they developed had to be for recording things on that people could see. Ottens denied that. He pointed to the existing equipment for capturing images on thin strips of film and tape (VCR). If you wanted people to accept video discs, they first had to learn and understand an entirely new technology. Ottens pointed to the picture and asked: "What does this thing look like?" The answer was obvious: a gramophone record.

While the LaserVision was still battling in the marketplace and Philips was losing the battle with an army of cautious software vendors, Ottens's small audio team was putting the finishing touches on the strange metaphor of an optical disc that you could listen to, but you couldn't watch (in the meantime, people are re-establishing the sound CD as an optical medium, for storing computer data, but also as a video disc).

$200 limit The further development of the video and audio discs kept pace at first, with Philips still assuming that the video side could become the most attractive. In 1976 the scales began to tip in favor of the audio disc. Then Lou Ottens learned from his co-workers that an optical audio player could be produced and sold for less than $200, a limit he had set for commercial viability. Moreover, digital technology was emerging that also improved sound and could make equipment less fragile and smaller.

The prototype of what must become the CD audio player was presented to Lou Ottens in 1976. It had the size and shape of a tele.vision device with lights. Ottens thought it was hideous. He ordered it to be made smaller. It had to be about the same size and as handy as a cassette player.

The Philips research team again put its shoulder to the wheel. From 1968 it had done nothing but steadily and methodically overcome technical problems. The CD audio player was made smaller and, in addition, digital encoding was built into it. Meanwhile, the passion for audio disc technology had taken hold of other companies as well: Sony was the most important of these. Ottens knew that Sony, after a one-year hiatus because the company had lost faith in it, was working on laser-display technology again.

He feared that if soon the world did not agree on one sy.steem, the same situation would arise again as with the videocassette recorder, a market in which the major electronics corporations fought each other through three different systems: VHS (from the Japanese company Matsushita), Betamax (from Sony, also from Japan) and V 2000 (from Philips). After a long and expensive battle, the VHS system of Matsushita's subsidiary JVC won the battle.

Ottens's fears of a one-size-fits-all situation were shared by Cor van der Klugt who had joined the Philips board of directors in 1978 (now president) and who foresaw another systems battle with Japanese competition if. a single standard was not established for all compact audio discs.

It was the time when the "Japanese hurricane" mentioned by Van der Klugt was raging in full force. This hurricane had driven all major American companies from the electronic field of hi-fi audio and video. Japanese companies controlled more than 90 percent of the hi-fi audio industry worldwide. Only in Europe did Philips still hold a strong position.

But even if Philips soU had the best CD technology, the company might still lose the race because of Japanese domination. The world would refuse to believe that a breakthrough in hi-fi audio could happen anywhere but Tokyo.

World standard Like Ottens, Van der Klugt therefore set a world standard for CD as his first priority. And there was really only one way to achieve this: cooperate with a major Japanese competitor. The most obvious was Matsushita, which, with the brand names JVC, Panasonic, Technics and National, was the largest and most powerful company in consumer electronics in the world. In fact, Philips was already cooperating with this competitor in various electronic components and in lighting products.

But Matsushita was probably too attached to its subsidiary JVC, which was working on a whole audio disc system of its own. Van der Klugt's preference therefore went to Sony from the outset, firstly because this Japanese competitor and had a reputation for quality and marketing, and secondly because of his personal relationship (A friendly rivalry') with Sony chief Akio Morita. In addition, Philips knew that Sony was very advanced in digital technology, which would be of vital importance to the purity of CD sound and which would come in handy to Philips. The rest of the technology the electronics, the optics, the lenses, the lasers, the plastics, and the idea of making the discs smaller than a single had been developed entirely at Philips.

But how was Sony to be packaged? Calling Morita would be a miss. That's why Van der Klugt took his toe-hold to "Zen politics": he turned to Morita by not turning to Morita.... Van der Klugt: "So we arranged a chance meeting with Akio Morita in New York. Akio Morita didn't know, but my friends and I decided to go into business with Sony, and I was the one to talk to Morita. But if I approached Sony directly and asked for something, I had lost my advantageous negotiating position. The moment I needed something, it was going to cost money. Therefore, we would not show that we needed something.

At that time, Akio Morita had a habit of dropping in on our directors in New York, in London, in Paris, in Milan. So I said: whoever hears from Akio Morita that he is coming by, should tell me. and then I will, quite by chance. also come and have a copy of coffee at your office."

Coincidentally So it happened that Van der Klugt 'accidentally' got into an animated conversation with Morita in New York about Brazille, where the Sony top man had just come from and where Van der Klugt himself had previously worked. The ice was broken and the conversation was steered toward the standardization of the CD. In the months that followed, there were and large number of follow-up talks between Philips and Sony. In the summer of 1979, cooperation was officially established.

Fraternally, in the following years, the final touches were added to the development of the CD player and record. The battle for the world standard had not yet been won. Theoretically, ten Ja-pan companies, plus Philips and Telefunken in Europe, were now involved in the race for thedigital audio disc. But in fact the battle was between Philips/Sony (with their CD system) and again Matsushita's JVC (with the AHD system). Finally, a major deciding factor would be the Japanese Ministry of Economic Affairs would provide. This sets all kinds of national standards within the framework of "NV Japan. The relevant committee of this ministry made the U-turn to this CD system after a demonstration by Philips and Sony in May 1980, according to Arthur D. Little's book. (Unfortunately, the book otherwise tells little about this crucial moment in the CD march, such as how it was lobbied by the Japanese government.)

Then, however, the biggest hurdle still had to be overcome: the record companies. If Philips and Sony could not get them to record their music on discs, there would be nothing to play and the excellent system would still flop.

Philips did have its own record company, PolyGram, which could start making CDs, but they alone were not enough. The four largest record companies in the world-CBS, Warner, RCA and EMI'-had to join in, in whole or in part.

Resistance In 1982, a few months before Philips and Sony were to launch the CD, the record industry's resistance to a new sound carrier, in which, after all, a lot of money must be poured, threatened to become unanimous. Van der Klugt received a nerves phone call from Akio Morita from Tokyo one Sunday morning, just as he was getting ready for a round of golf. He had gotten wind that the directors of all the major record companies in America would be meeting. The crucial thing about this meeting was not that the record companies would talk about the compact disc, but that they would all get together not to talk about the CD at all: they would make a kind of tacit agreement that they would let this expensive, new technology bleed to death by ignoring it. And there would be nothing to be done about that.

In the U.S., companies that collectively control three-quarters of the market can face severe penalties if they make joint tariff or other monopolistic agreements. But no action can be taken against a tacit agreement. Sony top executive Morita suggested that the record companies be given a free license on the CD record (it was three cents for Philips and three cents for Sony per record). But perhaps even that would be insufficient to break the record industry's resistance, he added.

A busy telephoning Van der Klugt then came up with an entirely different "poker game. He left Morita under the impression that he had another trump card up his sleeve, but did not tell him which it was. Only shortly before the meeting of the record executives in New York, when all parties knew by now that Philips had "something" up its sleeve, did he call his Japanese partner to reveal his strategy.

Van der Klugt told Mo-rita the following: "PolyGram is participating in the meeting of record executives in New York. They are taking two lawyers with them. Anyone who proposes a boycott can be subpoenaed. And he will be arrested the moment he leaves the room, because in the United States announcing a boycott (for industries) is a crime.

Perfect Van der Klugt's timing turned out to be perfect. He had waited until the last moment, so that no one else in the industry had had time to think out an effective countermove. The record companies' single-minded resistance was broken and the "every man for himself" policy that had previously prevailed was restored.

In November 1982, they jointly launched the CD player and the accompanying three-inch (twelve-centimeter) records. At that time, only 20,000 CD players were ready for use in the entire world and only 150 titles had been released on CD. The test case became classical music, especially that of Bach, Beethoven and Berlioz.

If Bach lovers did not buy CDs right from the start, Philips' huge investment in CD research and development was at stake. Many of them, of course, had also invested large sums of money in traditional recording and playback equipment and were therefore not immediately keen on the CD.

One struck a nerve. Herbert von Karajan, conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, made an impassioned plea for the CD. "With this," Karajan said, .everything else has become gaslighting." Philips and Sony could do something with that. The flattering remark was an excellent calling card to the market -and thus. the consumers.

Director Jan Timmer of PolyGram: "What the CD hi-fi fanatics did to him was to make them an illusion poorer. They believed that you could only get and spectacular sound by buying a spectacular installation at spectacular prices. But a CD you take home, you plug an en simple apparat into a mediocre sound system and then the miracle happens: an absolutely fantastic sound!" When more and more artists, including Mick Jagger, also began to demand that their music be recorded on CD, the gate was opened: one by one the major record companies switched to CD. production and the consumer went down on his knees for "the fantastic sound.

Royalties The breakthrough of the CD player had been achieved. All predictions of Philips and Sony, even the most optimistic ones, are now outdated. Philips' prediction that ninety million CD players would be sold in 1990 was already exceeded last year. In 1986, 136 million CD records were already sold in the world. And this Year, according to Philips, 15 million players and over 200 million records will be sold by all producers worldwide.

Philips and Sony obviously have the largest market shares in players. But also from the now more than 100 other producers in the world who have had to take over the system, the Dutch-Japanese developers will receive substantial amounts of royalties for the time being.